Are hydrogen-hungry microbes everything the body needs?

This post is part of "Boldly Growing," a Science of Fiction series about the future of food production and gastronomy. Check out the rest here.

If you remember anything about what humans eat in the 1999 film The Matrix, you probably remember feeling a bit grossed out. Most people in this dystopian, cyberpunk future live out their lives in a dream-like state, their minds trapped in a computer simulation of the late 1990s while their bodies float inside stasis pods, intravenously consuming the liquified remains of other humans. Those who have managed to escape the Matrix live in a sunless underground city where the only thing on the menu is a gruel-like slop made from a single-celled organism that produces "everything the body needs" — nutritionally, if not psychologically.

Obviously, I'd take microbial gruel over the rendered tallow of my fellow pod-mates, even if the Matrix can trick my mind into thinking the latter tastes like a delicious steak. But has anyone paused to consider why the people of Zion tolerate Siberian gulag fare day in, day out? It's great that nobody seems to be getting scurvy in this subterranean utopia, but are we to accept that humanity's most creative minds — people who managed to wake themselves up from an AI-run simulation that billions of others unblinkingly accept as reality — are powerless to make their nutrient-rich bacterial slop more appetizing?

That seems unlikely. Especially when you consider that there's a Finnish company working to perfect single-celled protein gastronomy right now.

That company is Solar Foods, an investor-funded startup on a mission to develop a sustainable food source that can feed future humans living on Earth, Mars, or in a post-apocalyptic cave using air, water, and electricity. Its product, called Solein, is a protein-rich powder derived from bacteria that's "nutritionally somewhere between dried meat, dried soy, and dried carrots," Solar Foods CEO Pasi Vainikka told The Science of Fiction. Neutral in flavor, Solar Foods' plan is to integrate Solein into a variety of different food products. Vainikka uses wheat flour as an analogy: "You never eat flour itself, but you make products out of it."

In the case of Solein, those products might be everything from cheese substitutes to egg replacements in pasta to meat alternatives.

Solar Foods didn't invent Solein because it was afraid a future machine takeover would destroy all photosynthetic life. Rather, the idea was born out of concern about the present-day climate crisis — and the outsized contribution our food system makes. Globally, nearly a quarter of humanity's greenhouse emissions are tied to agriculture and other land use activities, including 44% of global emissions of methane, a super-potent greenhouse gas. Food production consumes nearly half of Earth's ice-free land surface and 70% of the world's freshwater. Industrial agriculture is further responsible for polluting coastlines with excess fertilizer and degrading soils that contain enormous stockpiles of sequestered carbon.

Solar Foods's solution to this litany of problems is simple: Decouple food production from agriculture. On the small scale at which the company has tested its technology at least, that can be accomplished with bacteria that grow off carbon dioxide they pull from the air. Unlike plants, these bacteria don't require energy from sunlight to do so. Rather, they get their energy from hydrogen, which can be produced by splitting water in an electrolyzer.

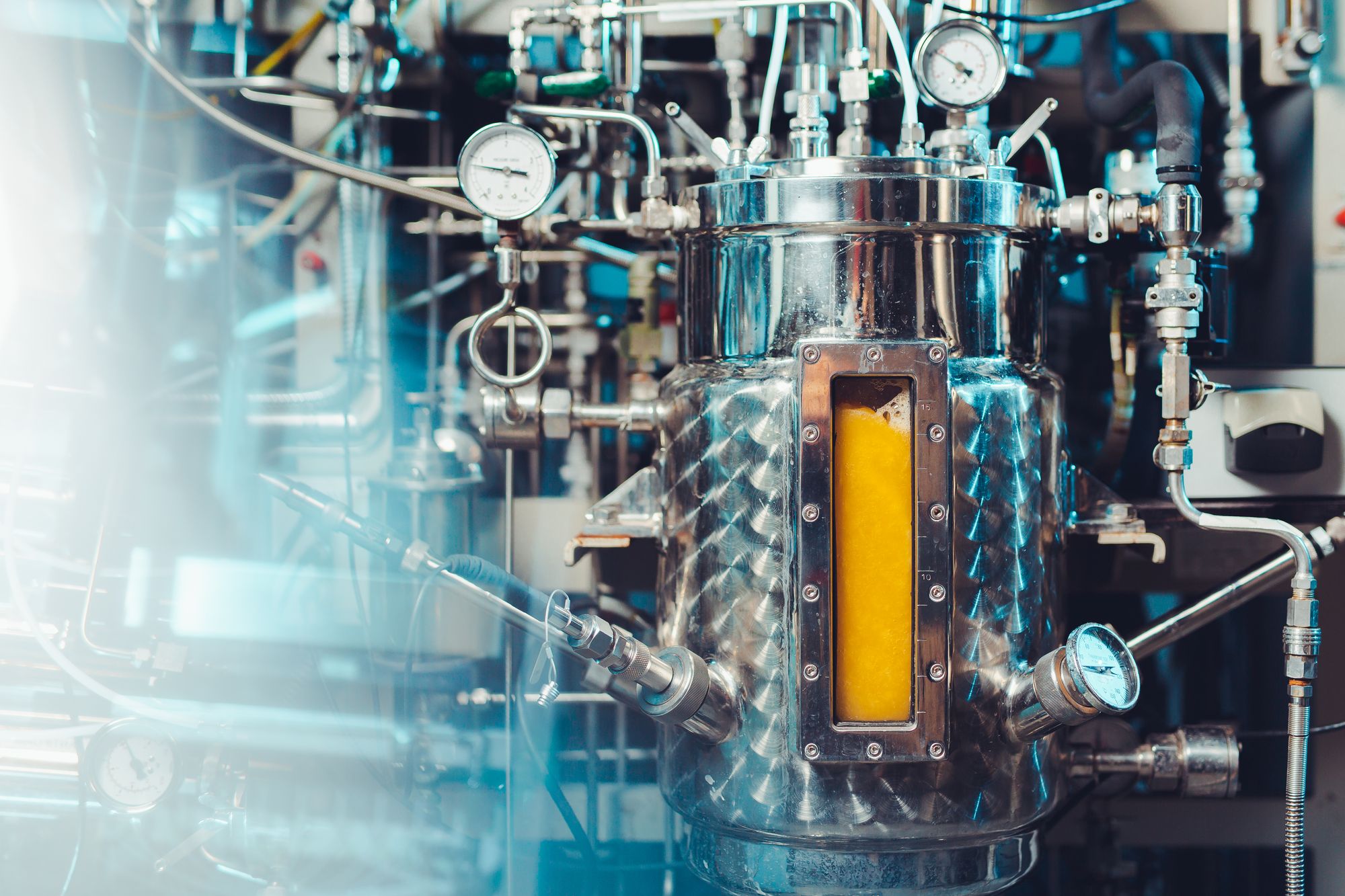

At Solar Foods' test facilities where a few kilograms of Solein are churned out each week, those electrolyzers are hydro-powered. At a demonstration facility expected to be operational by next summer, the hydrogen production process will be powered by wind energy. Along with nutrients and carbon dioxide captured from the air inside the plant, hydrogen will be bubbled into fermentation tanks to grow bacteria and produce about 100 tons of Solein a year, Vainikka says.

It's a far cry from the scale that's needed to eliminate conventional agriculture while feeding billions of hungry humans. But if the product catches on in even a niche market, the sustainability benefits could be significant. Solar Foods' internal research has found that Solein generates 200 times less CO2 emissions per kilogram of protein produced compared with beef while using 700 times less water and 200 times less land. Considering emissions, water, and land use, producing Solein is also considerably more efficient than growing crops, the company claims.

Vainikka says that Solar Foods plans to market Solein to the food industry rather than directly to consumers. That means you won't be able to purchase it in the bulk aisle of your grocery store, but you might one day spot it on the ingredient list of a meatless chicken nugget. Solein-like products might also be headed to space: Last year, Solar Foods was one of several microbially-focused concepts that won the first round of NASA's Deep Space Food Challenge, which provides prize money and recognition to teams that demonstrate innovative food production technologies that could feed astronauts on long-term missions. Several other prize-winning concepts focused on growing microscopic algae for food in deep space or on Mars — an idea that NASA researchers have been investigating for years due to the fast growth rates and high productivity of algae, and the possibility of using them in life support systems to generate oxygen and scrub CO2 from the air.

However, Ralph Fritsche, the spacecraft and exploration food systems project manager for NASA's Kennedy Space Center, feels that algae are more promising as a supplemental food source or a food additive rather than a staple of the future Martian diet. Research has shown that the protein content of edible algae from the genus Arthrospira is too high for them to serve as a dietary staple and that they may lack certain essential oils. "Trying to depend on it as more or less a primary source ingredient of the food system, I think, would be a challenge nutritionally and health-wise in the long run," Fritsche said.

The same concerns hold for bacterial foods like Solein, which is up to 70 percent protein by weight, an amount Vainikka described as "unnecessarily high." That's part of the reason he envisions the microbial product as a future food ingredient rather than something you simply mix with water and stick a straw in.

Pure microbial mush that's everything the body needs might be as unrealistic as it is an undesirable endpoint for the future of food. But if microbes grown in renewably-powered vats can provide some of our caloric needs while lightening humanity's footprint on the planet, it's worth taking the culinary possibilities seriously. At the very least, we should be able to make something better than Tastee Wheat.