Can ancient humans help save the planet?

A thousand years in the future, planet Earth is a hostile place. Miles-thick glaciers blanket the continents, leaving only narrow strips of coastline warm enough to support life. There, a menagerie of Ice Age monsters skulk the frozen forests, hunting and being hunted by groups of nomadic humans. Something even deadlier lies offshore: the zyme, a glowing green algae that coats the oceans like slimy quicksand, swallowing any ships that dare venture into its domain.

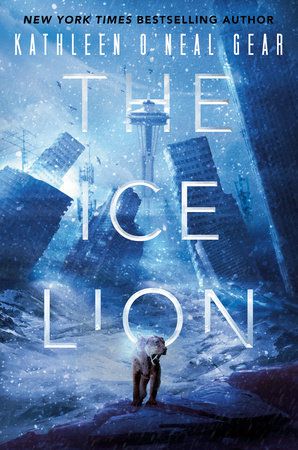

This is the mesmerizing world archaeologist Kathleen O’Neal Gear has brought to life in her recent novel The Ice Lion, a genre-bending work of fiction that’s both a cautionary tale about the future and a vivid re-imagining of human history. The Ice Lion tells the story of Quiller and Lynx, two best friends from the Sealion tribe who begin to unravel the mystery of their existence after a group of lions attacks and slaughters several members of their village, including Lynx’s wife.

Like the predators that hunt them, Quiller, Lynx, and the rest of the Sealion people are ambassadors from the distant past: In their case, archaic humans called Denisovans. By revealing the world through their eyes — eyes that see cosmic battles between ancient gods where readers will glimpse a world remade by a catastrophic climate experiment — O’Neal Gear shows the humanity of people many wouldn’t consider entirely human. Perhaps, she suggests, getting to know these forgotten ancestors could help us save the future.

In truth, we know very little about who the Denisovans were. Their existence was first announced in 2010 when scientists sequenced mitochondrial DNA from a previously unknown hominid’s finger bone at Denisova Cave in southern Siberia. A few other bone fragments from the same cave, and a jawbone from Tibet, comprise the entire physical record of the species. Genetically, we know that Denisovans were more closely related to Neanderthals than they were to modern humans, and we know that these two hominids interbred. We also know that Denisovans interbred with Homo sapiens because their DNA can be found in people of East Asian descent, particularly in Aboriginal Australians and New Guineans.

But as for how Denisovans lived, we’re largely in the dark. In The Ice Lion, O’Neal Gear imagines a society of nomadic hunters who build tented structures from mammoth bones and stretched hides, hunt using bone-tipped spears, cook over fires, and bury their dead. Broadly speaking, this isn’t so different from the technology Neanderthals had tens of thousands of years ago: wooden spears and axes with sharpened stone tips, bone tools, fires for cooking food (although whether Neanderthals started them is a matter of debate), and, at least on occasion, open-air constructions. Rebecca Wragg Sykes, an archaeologist and the author of Kindred: Neanderthal Life, Love Death and Art, says that Neanderthal technology is a reasonable starting point for imagining how Denisovans might have lived, considering that some Neanderthal technologies, like the prepared core technique of making stone tools, were developed quite early — perhaps, before Neanderthals and Denisovans diverged into two distinct species.

“If we’re assuming there is a sort of technological shared origin, then I would expect there to be woodworking, this prepared core technology, and maybe some bone [tools]” among Denisovans, Sykes told The Science of Fiction. After the ‘Neandersovan’ lineage split 450 to 500 thousand years ago, Denisovans could have continued to develop their technology further.

In a sense, Sykes says, the dearth of evidence for what sort of technology Denisovans had “leaves things open and up for grabs for a novelist.”

If we know very little about the tools Denisovans used, we know even less about the sorts of societies they, and other early hominids, formed, including any shared spiritual beliefs, artistic traditions, or ritual practices. O’Neal Gear’s Sealion tribe is a highly spiritual group of people who believe in a cosmic afterlife, paint sacred clan symbols on their shelters, and have a complex mythological origin story passed down by elders. The plot revolves around the pacifistic young Lynx being sent on a spirit quest after having an out-of-body experience during a lion attack.

We can’t say whether the real Denisovans had such rich inner lives. We can’t even say whether the Neanderthals did, and we’ve been studying them for over a century. Sykes says that Neanderthals clearly had a sense of aesthetics, but it’s tough to say whether they made the cognitive leap from creating aesthetically pleasing objects to creating things with a shared or symbolic meaning.

“They were really interested in the qualities of materials,” she said. “But as far as we can see, there is no external framework of agreed meanings which would turn it into something a bit more systematic in turns of symbolic content or art traditions.”

That said, new discoveries are constantly changing our understanding of what Neanderthals were cognitively capable of. Recently, a team of researchers discovered a 51,000-year-old deer foot bone at a cave in Germany with decorative engravings that appear to have been etched by Neanderthals — evidence, the scientists argue, that these early humans “were capable of creating symbolic expressions.”

Debates over Neanderthal spirituality, meanwhile, were reignited several years ago when a team of scientists determined that an archaeological cave site in France featuring rings and mounds of broken stalagmites is so old—176,500 years old, to be exact—that it must have been built by Neanderthals. The site doesn’t appear to have been inhabited, but people clearly put many hours of labor into its construction, leading some researchers to speculate it was used for ritual purposes.

While there’s still much we don’t know about the early hominids that live on in our DNA, the more we learn, the more unfair stereotypical portrayals of Neanderthals and their cousins as unsophisticated brutes seem to be. O’Neal Gear’s Sealion people may or may not be an accurate reimagining of the Denisovans, but their technological and cognitive complexity certainly fits with our evolving understanding of our distant ancestors.

And while the lives of these ancient hominids may seem like a subject of narrow academic interest, unraveling their story could help us confront many of today's most pressing problems, from racism and bigotry to climate change. The disappearance of Neanderthals and other early hominids, Sykes says, has helped fuel an origin mythology about Homo sapiens: that we won the evolutionary game because of our biological superiority and domineering nature. This notion that humanity is somehow destined to dominate other life forms has defined the last two centuries of extractive capitalism and is a key reason we are now on the brink of a sixth mass extinction, spiraling toward climate ruin.

But not all archaeologists agree that Homo sapiens outlasted other hominids because we were smarter and better than them, nor is it at all clear that Neanderthals and Denisovans were violently extirpated, as many have suggested. Sykes points out that while we used to believe Homo sapiens turned up in Eurasia just before Neanderthals vanished, newer evidence suggests there were earlier, failed migrations out of Africa during the heydey of Neanderthal civilization. Almost all of those first pioneering Homo sapiens are “gone in genetic terms,” Sykes said. “They are more extinct than Neanderthals.”

That fact is hard to square with the idea that our species was biologically programmed for success, vanquishing other humans whenever we made contact. The alternatives—that early interactions between hominid groups were often peaceful; that our species survived where others didn’t more out of luck than talent—paint a much humbler picture of our place in evolutionary history and make our future survival seem far less certain.

“There has been a tendency to assume that any interaction we had with [other hominids] was going to be based around conflict or one group dominating, as in us,” Sykes said. “And there still isn't direct evidence for that. So the stories we tell ourselves about where we came from? Maybe we should critique them. Because those narratives really shape what we think our future possibilities are.”

In The Ice Lion, Denisovans are resurrected as a last-ditch effort to save humanity. Perhaps learning more about why they disappeared can help us do the same.