How a videogame taught my generation that Earth is alive

Like many environmental scientists, early exposure to nature sparked my interest in the field. But so did the 1990 video game SimEarth, game studio Maxis's first release after SimCity. SimEarth was more than mere entertainment, however. It was Maxis co-founder Will Wright’s effort to disseminate an idea that captivated him: The Gaia Hypothesis, which proposed that Earth is alive.

Developed by NASA astrobiologist James Lovelock and microbiologist Lynn Margulis, a pioneering researcher on the origins of life, the Gaia Hypothesis sounds more like New Age spirituality than science. But in the 1980s and early 1990s, many stolid Earth scientists took it seriously. NASA credits Gaia theory with helping spur the development of Earth system science, the field that explores how our planet's atmosphere, oceans, ice, rocks, and ecosystems interact and shape each other. Wright, who saw himself as something of a science popularizer in the mold of Carl Sagan, wanted everyone to know about it.

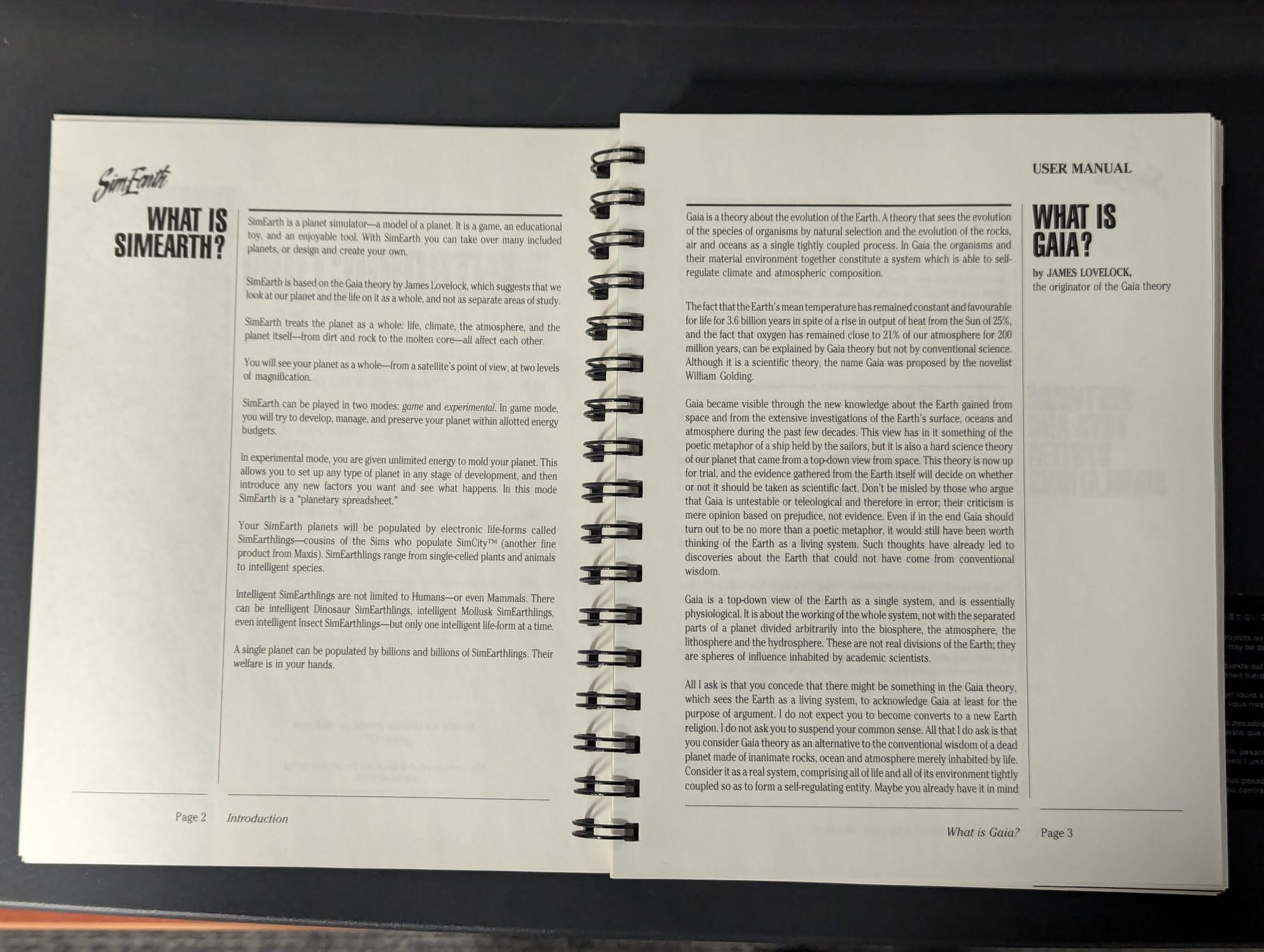

"SimEarth gives you the chance to enter the Gaia argument as a player," Lovelock wrote in an introductory essay for the SimEarth Bible, a 224-page aftermarket strategy guide published in 1991, a year after the game's release. Lovelock, who consulted with Wright during SimEarth's development and whose "Daisyworld" model appears as an in-game tutorial, considered SimEarth a sophisticated representation of the planet on par with global climate models.

Of course, as a seven-year-old booting up SimEarth on my family's Performa Macintosh computer, I didn't know any of this. I just saw a pixelated garden of possibilities.

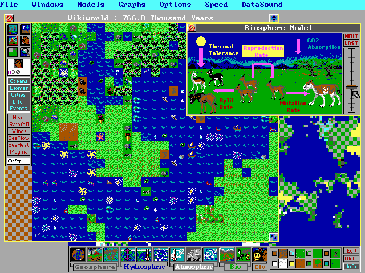

The game simulates the evolution of a rocky planet with geologic activity, weather systems, and oceans. As the planet's non-living systems evolve, so do its life forms, which start as single-celled prokaryotes but can eventually become sapient animals capable of launching nukes or blasting off into space. The planet's living and non-living systems interact: The spread of plant biomes, for instance, releases oxygen into the atmosphere while drawing down carbon dioxide; if too much carbon is sucked down, plant growth is inhibited and the biomes contract. As CO2-consuming plant life declines, carbon builds up in the atmosphere once more. Eventually, the planet's biomes bounce back, illustrating the Gaian idea that life regulates the non-living environment.

Players can intervene in global affairs by altering the atmosphere and landmasses, placing animals or biomes, or triggering cataclysmic events like volcanic eruptions. They can select a scenario with a goal, such as helping an Earth civilization advance or terraforming a Venus-like planet. Or, unlike most other video games, they can do nothing, and watch the simulation play out. As SimEarth programmer Fred Haslam put it in a 2009 article, "players could frequently win without touching a key."

I never played with dolls, and The Sims—the dollhouse simulator that eventually took over the Maxis brand—didn't interest me. But this geologic drama that put the fate of ecosystems across eons at my fingertips? This was riveting.

Not everyone at Maxis felt the same way.

SimEarth "was a science fair project," Maxis co-founder Jeff Braun told The Science of Fiction. "Fun was not the goal."

Braun wanted Maxis to capitalize on the commercial success of SimCity with a sequel. SimCity was an unconventional video game, but it gave players a sense that they were creating something uniquely theirs. This, Braun felt, was key: "When you use the word 'my', I'm all on board," he said.

But planets have a life of their own. And Wright, who had read Lovelock's writings on Gaia and struck up a correspondence with him, found that fascinating.

Wright "appreciated that this [Lovelock] guy is a programmer and a scientist and had something interesting to say," Braun said. "So Will really wanted to give him some visibility...get that message out there far and wide that the Earth is alive."

James Lovelock's introduction in the SimEarth gameplay manual. Credit: Phil Salvador

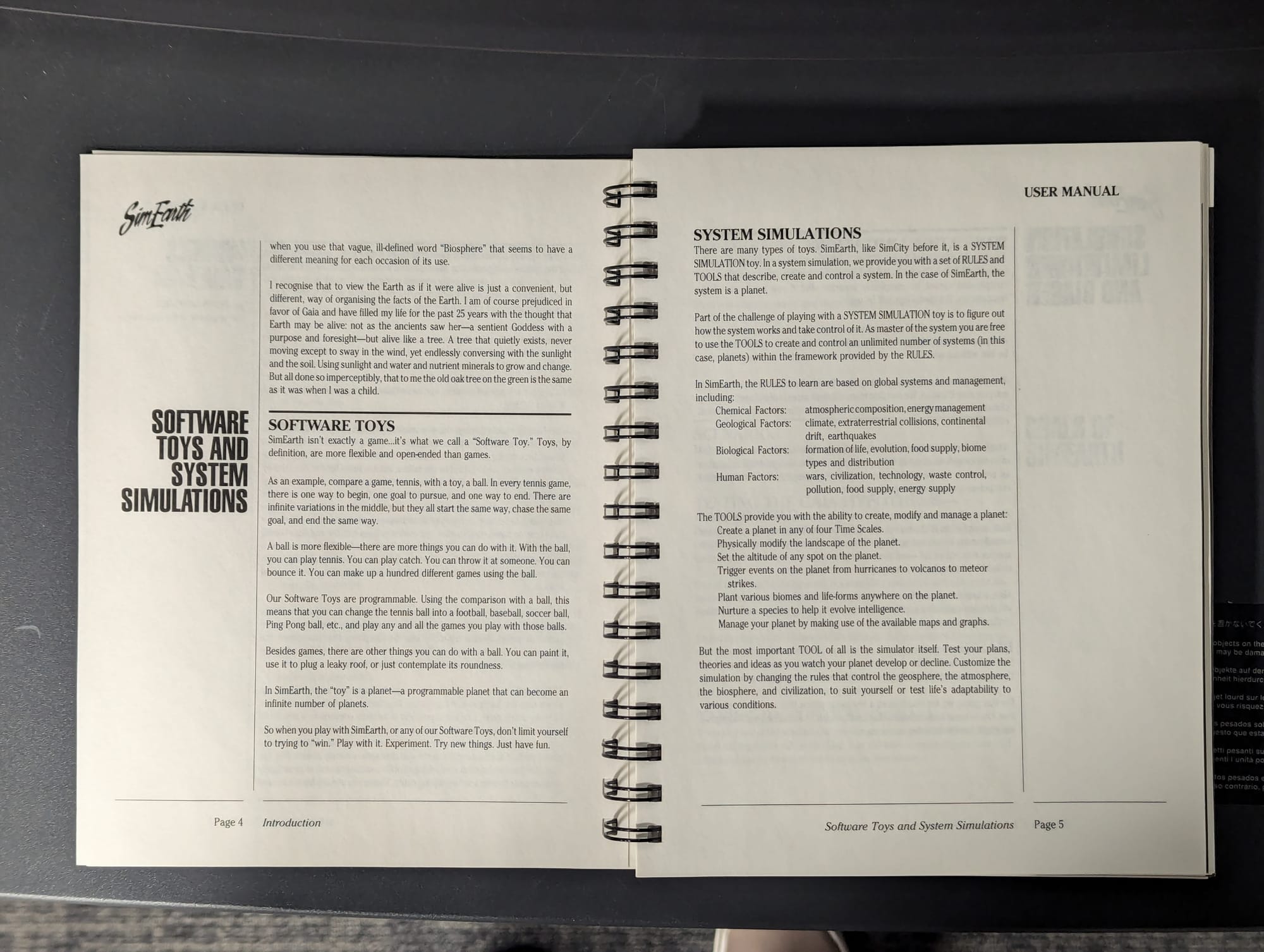

But Braun, who was focused on growing the business, worried Wright's message would get lost if the game didn't sell. And so he "went into damage control" mode. He asked Michael Bremmer, Maxis's lead manual writer, to "go big" for SimEarth. The subsequent gameplay manual clocked in at 228 pages. Not only did it cover how to play the game and how the simulation worked, but it included a lengthy "Introduction to Earth Science" section, with chapters on geology, climate, Gaia, and more. Lovelock wrote an introductory essay and provided design assistance.

Carolina Lithgow-Bertelloni, who now chairs the Department of Earth, Planetary, and Space Sciences at the University of California, Los Angeles, also contributed. Lithgow-Bertelloni was hired to write the manual's geology section while she was a grad student at UC Berkeley. While she doesn't remember much about the writing process, she does remember how she felt about it.

"I was pretty proud that I was asked to do this," Lithgow-Bertelloni told The Science of Fiction. "For a long time, I even listed it on my CV."

The contributions of experts like Lovelock and Lithgow-Bertelloni gave SimEarth scientific credibility. Braun decided to lean into this by shopping the game to schools. He entered a distribution agreement with Davidson & Associates, the edutainment software company that produced the Math Blaster! games. And he hired education entrepreneur Bobbi Kurshan to design a curriculum for high school and college students based on SimEarth. While the curriculum was intended for Earth science classrooms, the game wound up being played in a wide range of science, math, and geography courses, according to Kurshan.

"It became a blockbuster product in schools," Kurshan told The Science of Fiction.

Scans of a teacher's guide that includes SimEarth-based lesson plans. Credit: Guide courtesy of Michael Bremmer

While it may sound unusual for a video game company to hire geologists and educational consultants, this was in keeping with what Maxis was doing with other Sim titles at the time, according to video game historian Phil Salvador. SimCity's various strategy guides and manuals were full of information about urban planning, while the manual for a later release, SimIsle, included essays on rainforests and conservation. Maxis was "always interested in enhancing the users' experience by delving more into these topics," Salvador said.

Wright was also interested in supporting organizations he felt aligned with. As game designer Chaim Gingold notes in his book Building SimCity, Maxis supported Lovelock's work by contributing royalties to his charity. Early versions of SimEarth even included registration cards that encouraged players to select an environmental organization for Maxis to donate $1 to on their behalf.

One of the organizations players could choose was Earthwatch, a nonprofit that supports global environmental research by connecting volunteers with scientists. The group received a one-time donation of $3,794 in May 1993, Heather Wilcox, who directs charitable giving for the organization, told The Science of Fiction. Wilcox added that a gift of that size was probably equivalent to over $10,000 today, "which would be considered a significant gift to us."

"I think it’s safe to say that SimEarth’s fundraising efforts on our behalf likely helped to ensure that a wide range of important conservation research efforts were able to get the funding they needed to carry on for another year," Wilcox said.

Another of the environmental groups players could donate to, Earth First!, has a history of using controversial methods, like sabotage, to protest humanity's abuse of nature. It is unclear how the group earned a spot on the Sim Earth registration cards or whether Maxis received any blowback over the radical pick.

While SimEarth was scientifically ambitious, perfection wasn't the goal. Many aspects of the planetary model are vastly over-simplified, while others are just plain wrong. For instance, SimEarth's geologic model includes a "massive upwelling event" every 30 million years that triggers a spate of earthquakes and volcanic activity around the world. There is no evidence for any such recurring tectonic shakeup on Earth.

The Gaia Hypothesis, meanwhile, has fallen to the scientific fringes in the 35 years since SimEarth's release. Yet ideas from it live on. Earth scientists now understand that the planet maintains habitable conditions partly through a series of "feedback loops," just as Lovelock and Margulis proposed. The search for life on other planets, meanwhile, was shaped by the Gaian observation that biological processes leave chemical fingerprints in the atmosphere.

The Gaia Hypothesis also left an impression on young people. I can't be sure that watching pixelated planets evolve from barren rocks to industrial civilizations is the reason I wound up majoring in ecology in college or pursuing a career in environmental journalism. But early exposure to the idea that the planet is alive, and that its life support systems are fragile, surely had an impact.

Reflecting on Sim Earth decades later, Haslam wrote that if he and Wright had "considered the impact this game would have on a generation of students, we probably would have panicked and never finished the project. But we did finish it, filled as it is with both flaws and insights."

I, for one, am grateful they did.