How a biologist invented the fabled fauna in Jeff VanderMeer’s new eco-thriller

Meghan Brown never imagined herself inventing fictional organisms. The biology professor at Hobart and Williams Smith Colleges spends most of her time teaching ecology to undergraduates and studying real organisms that inhabit freshwater lakes. Sure, she helped her kid make a giant blue slug costume for Halloween one year, but he was the one who actually imagined the mythical monster.

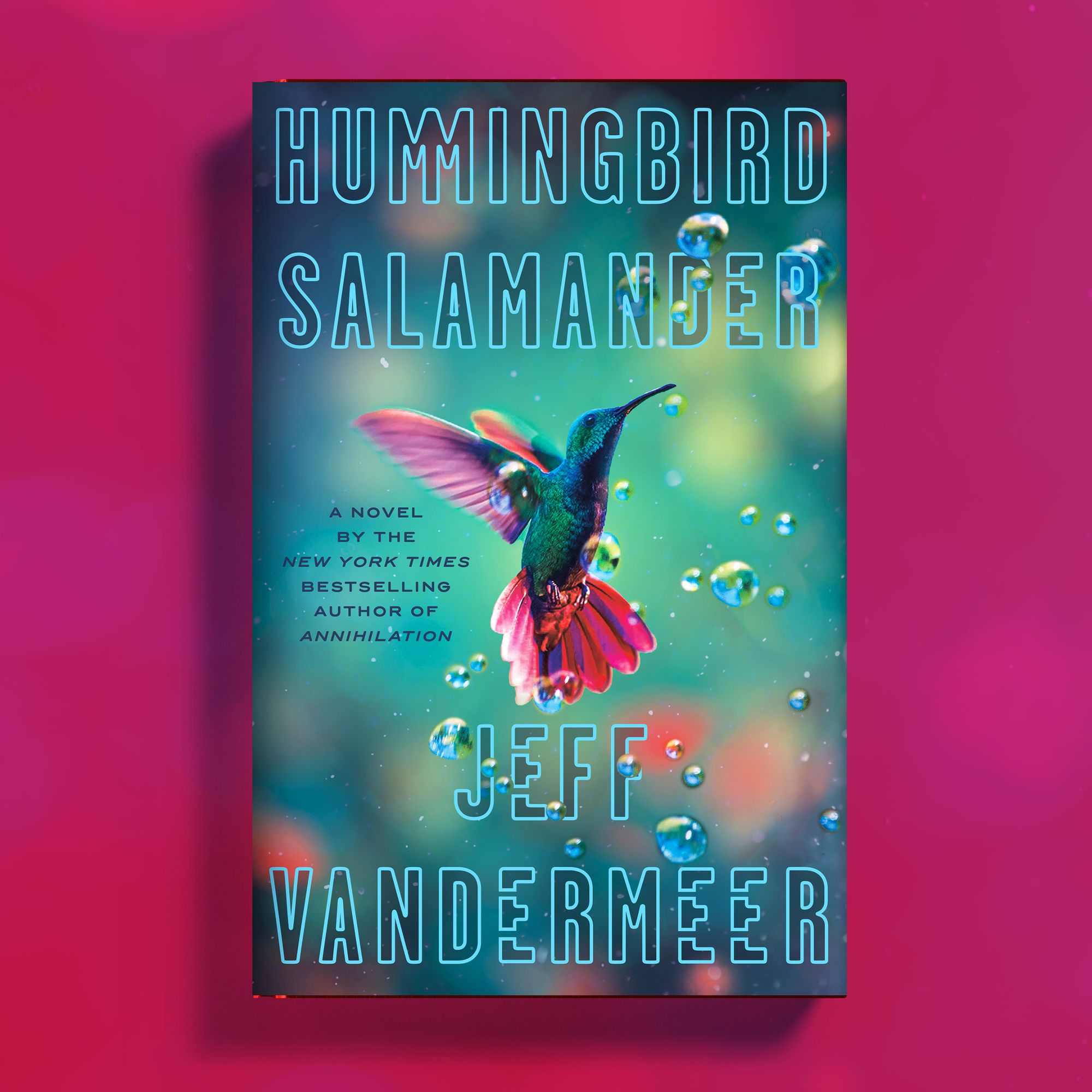

It was different when acclaimed novelist Jeff VanderMeer, author of the bestselling Southern Reach trilogy and Borne, asked Brown to invent from scratch the animals that would be at the center of his new eco-thriller, Hummingbird Salamander.

Brown had little experience writing fiction and even less making up species. But she took on the assignment gamely and wound up creating two fictional organisms — the naiad hummingbird Selastrephes griffin, and the road newt Plethowen omena — that, despite a few idiosyncrasies, are strikingly realistic. Ultimately, Brown’s contributions had a major impact on the novel, with VanderMeer weaving snippets of her descriptions into the text and using the biological traits she created to drive the plot forward.

“When I read that first draft and [realized], oh my gosh, my words are in this book and people are going to read it, I was nervous,” Brown told The Science of Fiction. “But it was also exciting. And it was a joy to be able to write language that wasn't intended for a scientific audience, but was saying the same thing in a different color palette.”

A psychological thriller with an ecological bend, Hummingbird Salamander follows Jane Smith, a security researcher who abandons her banal suburban life after she receives a taxidermy hummingbird along with an enigmatic note suggesting the existence of a companion salamander. As Jane attempts to unravel the mystery of the hummingbird, the salamander, and Silvina, the dead ecoterrorist who left Jane a treacherous trail of taxidermied clues, she becomes enmeshed in a web of wildlife traffickers, rogue government agents, and fossil fuel kingpins. All the while, the world around Jane unravels as intersecting crises of climate change and mass extinction fuel megafires, disrupt ocean currents, and spark pandemics.

It’s a world that will feel eerily familiar if you happen to read the news or go outside occasionally. Still, VanderMeer manages to package it all into an engrossing and unexpected tale by revealing the world through the eyes of an environmental naif who is at once discovering the mesmerizing beauty of nature and the ineffable tragedy of its destruction. As the novel progresses and Jane learns more about the incredible lives of the animals that upended her own life — the naiad hummingbird makes a 6,000-mile migration from the Andes to the Pacific Northwest every year; the road newt is a mythical giant whose very existence has long been the stuff of legend — she becomes grief-stricken at the idea that people drove both species extinct through carelessness and greed.

VanderMeer knew early on that he wanted the book to revolve around a hummingbird and a salamander. “Basically I chose them because they're so completely different,” VanderMeer told The Science of Fiction. “But they put a spotlight on two aspects of our current condition.”

Hummingbirds, some of which make epic trans-continental migrations, highlight the fact that if we don’t have large wildlife corridors for species to move through, we risk losing a lot of biodiversity. Salamanders, many of which breathe through their skin, epitomize a different sort of fragility. “They're very susceptible to any kind of contamination of their environment by pesticides, herbicides and things like that,” VanderMeer said.

But to make his invented animals more than one-dimensional allegories, VanderMeer needed a scientist’s help. He knew Brown from spending a semester at Hobart and Williams Smith College as a teaching fellow, during which time the two collaborated to explore how creative writing could be used to teach undergraduates about ecology and evolution. When VanderMeer told Brown he needed a de novo hummingbird and salamander for his upcoming novel, she saw a chance to “have a student audience that's much broader than what I teach in a typical semester,” Brown said. “That's an awesome opportunity.”

To bring her fictional creatures to life, Brown started by consulting their real world cousins. “They had to be conceivable,” she said. “They had to be convincing to me, as a biologist. So I was probably subconsciously making sure that they obeyed things like thermodynamics and gravity and really consciously thinking about how they fit into the evolution of what already existed.”

For the road newt Plethowen omena, Brown borrowed traits from the genus Plethodon, woodland salamanders that are native to North America. Those traits include trading lungs for the ability to exchange gas through their skin, which allows the salamanders to forage continuously without stopping for breath, and an ability to jettison their tail from their body in order to distract predators while making an escape. The naiad hummingbird Selastrephes griffin, meanwhile, is one of several hummingbirds that migrates every year from a winter home in South America to breeding grounds in North America, aided in its ultra-marathon journey by a warp-speed metabolism. Serendipitously, Brown visited both British Columbia and the Andes during the year she was developing the Selastrephes griffin, allowing her to incorporate flora, fauna, and environmental conditions she experienced in the field into the animal’s biology.

While Brown strived to keep both animals as scientifically plausible as possible, she also sprinkled in a few Easter eggs. Plethowen omena, for instance, gets its common name from the double yellow line running down its spine — a warning to predators that the animal is toxic that also helps it blend in with the man-made roads that criss-cross its habitat. The hummingbird’s name, meanwhile, is steeped in lore: naiads are winged human-like creatures from Greek mythology; the griffin is a mythical mashup of a lion and an eagle.

Eventually, Brown handed VanderMeer a dossier containing descriptions of both species (edited versions of which can be found here). VanderMeer liked Brown’s writing so much that he pulled some of the text verbatim into the novel, presenting it as information Jane discovers while conducting her own research.

We think of fact and fiction as being this dichotomy, but there really is a continuum

“I think I actually used more of her material than I would have if I'd written it myself, in part because it was such a different perspective and style,” VanderMeer said. After some feedback from Brown, who read an early version of the novel, VanderMeer also decided to incorporate aspects of the animals’ biology into its dramatic conclusion.

“Jeff and I collaborated on the ending to capitalize on things that had already been created and laid out in the book that I saw as a biologist,” Brown said. “So that was super cool for the book. But it was also really neat for the collaboration.”

The collaboration worked out so well, in fact, that the two are planning to work together again for VanderMeer’s next novel, which explores a situation where the ocean is so full of plastic that certain life forms have evolved to thrive in the garbage stew. Brown’s expertise in how humans have degraded aquatic environments makes her an ideal partner for the project, VanderMeer says.

Brown, meanwhile, sees her new side-gig as an animal inventor as a way to hone her science communication skills — and ultimately, do better science.

“We think of fact and fiction as being this dichotomy, but there really is a continuum,” Brown said. “When you're a scientist trying to understand extraordinary things like deep sea life or hummingbird migration, or you're trying to understand things that are possible but not yet actualized—remediating a pond, coming to a climate neutral future—the implausible world is a really great model to be in and spend time in.”