Hallucinations-on-demand, artificial reefs: How science fiction is inspiring innovation

Dan Novy wants to disrupt your entertainment experience. The Emmy Award-winning visual effects supervisor-turned-MIT research scientist is tired of everyone sitting around mindlessly binging Netflix—he wants us to be able to see, feel, and interact with the fantasy worlds we love. He wrote his PhD thesis on “programmable synthetic hallucinations,” or how to trick the human brain into thinking it’s been transported into an alternate reality. There are no mind-altering drugs involved, just magnetic fields stimulating the right parts of the visual cortex.

It sounds like something out of science fiction—and in fact, it kind of is. Novy’s dissertation was inspired by the Penfield Mood Organ, a device from Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? that allows users to dial in any mood they want to experience. Novy suspects we’re still a few decades away from being able to write holodeck programs directly into our brains without invasive hardware, but thanks to Dick’s passing mention of a consciousness-altering device in his novel, along with other sci-fi examples like William Gibson’s Neuromancer, there is now an MIT doctoral thesis describing how it might be done.

When Novy isn’t drawing on science fiction to inspire his own work, he’s teaching students to do the same through SciFab: Science Fiction-Inspired Prototyping, an MIT Media Lab course he co-teaches with Joost Bonsen. The Science of Fiction spoke with Novy to learn more about the interplay between science fiction and innovation, the futuristic technologies students at the MIT Media Lab are bringing to life, and what programmers can learn from magicians.

This interview has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

Maddie Stone: Science fiction has clearly played a role in shaping your career path. Can you tell me a bit about what you see as the relationship between science fiction and innovation more broadly?

Dan Novy: For me, I always say science fiction has a mutagenic effect. So instead of a one-to-one relationship of like, ‘oh, there were the communicators and Star Trek and that led to the inspiration for the StarTAC flip phone.’ I have a whole lecture full of those where I go through and say ‘this person was inspired by this to do this.’ Like the submarine was literally somebody reading Jules Verne and going ‘aha.’ The first true production submarine was directly inspired by Jules Verne.

So there's all of those sort of one-to-one mappings. And I'm much more interested in the sort of nebulous way ideas go into your head and ferment into a fine whiskey. And because you've been reading these ideas that may not be possible now, they are at least exposing you to a much broader vector of approaches. So you are sort of priming your own imagination and your own self to be able to innovate or deliver a solution to a problem. People often say using hallucinogens will expand your mind. I believe science fiction expands your mind in the same way completely non-chemically.

If you've never read a science fiction story about a generation ship or an ark ship which needs to last for generations, I believe your approach to, say, city science or urban urban engineering will be stunted in some way. Science fiction can lead you to a more expanded series of approaches to any design problem. It gives you just a huge array of alternatives.

Maddie Stone: You teach a course at the MIT Media Lab called ‘Science Fiction-Inspired Prototyping’. Can you tell me a bit about how the course is structured, what do students learn and what they do in it?

Dan Novy: So the course was originally created by myself and Sophia Brueckner, who is now a professor at the University of Michigan. At that point, it was called ‘Science Fiction To Science Fabrication’. And she created a version of the class at the Rhode Island School of Design. So she had her students reading science fiction and then doing design exercises based on the reading. And I heard about that and I was like, woah, this is crazy. We should make this an engineering class here at MIT. And she was a Media Lab master's student at the time.

The first iteration [in 2013] was to read science fiction stories and then find something in the science fiction that was perhaps not possible or not recognized as important in some way and then build it, make it real.

So the example I give for this often is in 1945, Arthur C. Clarke, who's a radio operator, writes a science fiction story about how an artificial moon or a telecommunications satellite should operate. Twenty years later, almost to the day, Early Bird goes up and it operates almost exactly how he describes it in the science fiction story. [Editor’s note: Early Bird is the nickname for Intelsat 1, the world’s first communications satellite.] And it helps that Clarke was a radio operator and he understood how it needed to work, but it took 20 years between the science fiction story to when it became a reality. And what we want to do is collapse that 20 years to zero years. We want to make that happen now.

There is kind of a spectrum of projects. On the more speculative side is the design fiction where you're going to create a user interface for, say, a computer system or a flight system that maybe doesn't and can't exist right now. So, say matter replication works. We've got replicators like on the Enterprise or in [Neal Stephenson’s] The Diamond Age. They look like a microwave oven, right? So you've got a keypad and you hit the buttons and you wait, it even hums sometimes. Then you open the door and you pull out your tea, Earl Gray, hot. It was designed like that because we have microwaves. So that was a way for you to understand how it could work. But does it need to work that way? So sometimes there's these questions of, well, imagine the technology already works, I want you to create how you think a human being would operate it. So that's one side of the spectrum, in which case you're building web interfaces or some kind of GUI perhaps that shows how it works.

And then all the way at the other end is, oh, wait, I'm pretty sure I can actually make this a real thing, and then you build it.

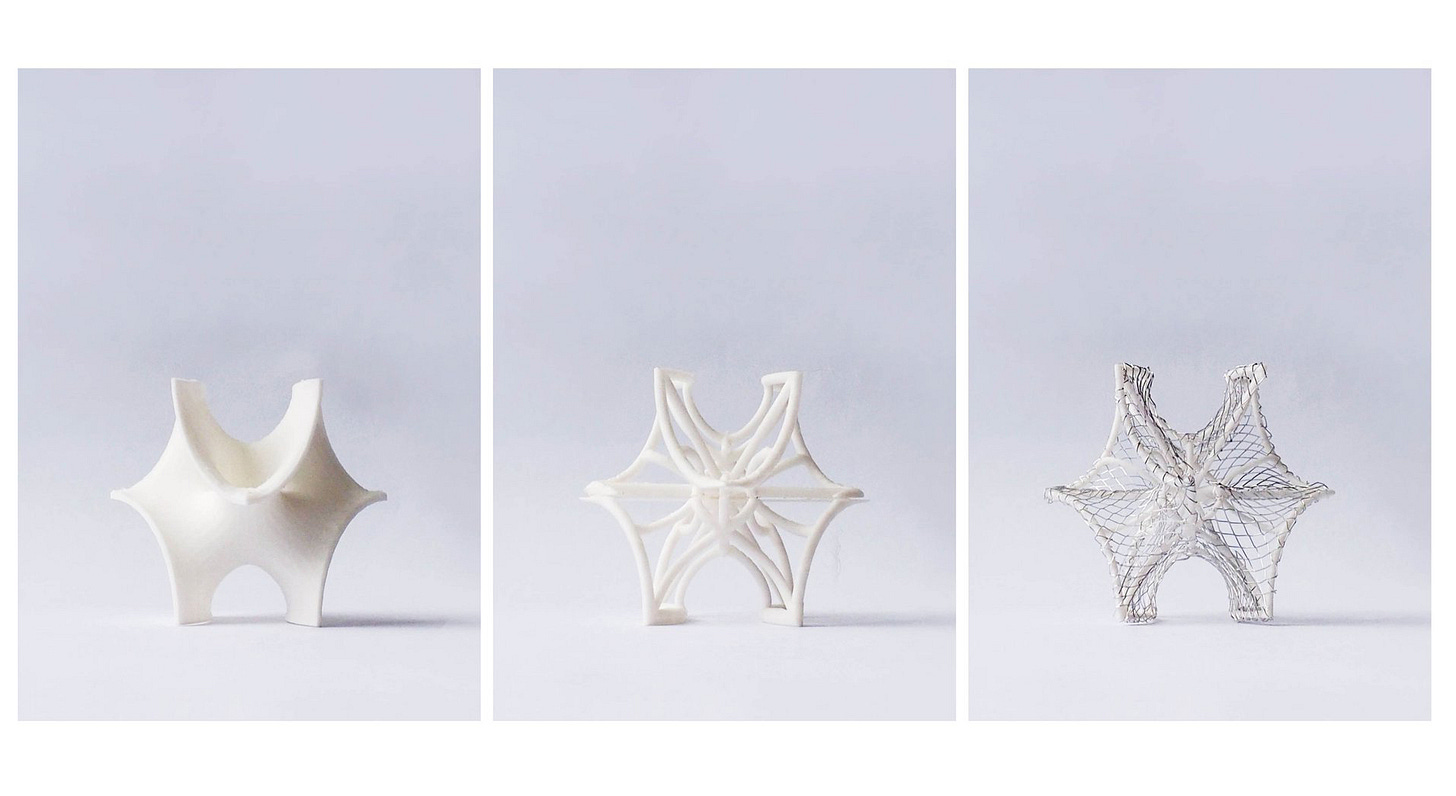

So for example, I do deep ocean exploration as well. And I'm super into what they call Biorock, which is where you run a current through a metal mesh and it pulls calcium carbonate out of seawater. And that actually acts as a scaffold for coral growth. So you can accelerate coral growth or create artificial coral reefs using this. And then the other half of the equation is if you break a piece of coral in half, it'll actually try to grow back faster. And so if you continue to break them in half, you just keep going half and half and half, you can actually accelerate the regrowth. That's coral microfragmentation.

So I had a student, and he was like, I don't know what I want to build for your class. I'm like, well, how about this? And he got fascinated by it. So he literally, in a tank, did a bunch of work with space filling curves to try to maximize the amount of area that he could have. And then he put the electrodes on and he started growing the Biorock and then he started doing the microfragmentation and he was actually able to get coral growth that was at least twice, if not more, faster than it would normally grow, which is super important for coral reef remediation. And this, of course, was inspired by the Imperial Tectonics corporation from The Diamond Age, where they grow islands. They make real estate using this sort of smart coral. And for his final project, he built the first baby step of that.

People often say using hallucinogens will expand your mind. I believe science fiction expands your mind in the same way completely non-chemically.

Maddie Stone: What do the students in this class typically go on to do? Are they mostly engineers who are interested in applying these skills to actually design new devices or machines, or is it more people from the film and art world, or a mix?

Dan Novy: It's a huge mix. It's generally designed for a Media Lab master's student. Some people then leave and go out into industry. Some people go on for the PhD. But we have undergrads from MIT that want to take the class. A huge amount of the Graduate School of Design from Harvard comes and takes the class. We have students from Wellesley and we have students from the museum school at Tufts. So it really is very much a Media Lab approach of there is engineering, there's design, there's art, there is science, and none of them are above the others. And if you're good at one, hopefully we're going to teach you something that encourages growth in the others. And so we have them play to their strengths, increase their knowledge in the areas that they're not strong in, but then create something of substantive value to them in their academic career as well.

Maddie Stone: Can you give an example or two of projects you've seen get developed further beyond the class, whether it's in a design setting or maybe for an art exhibit or even a patent?

Dan Novy: So one that comes to mind is Joy Buolamwini, she is the head of the Algorithmic Justice League. So there was a class assignment where we use a game called Thing from the Future, created by Situation Lab. And it's a game of prompt. And the prompt was she had to create a mirror that showed her true inner self. And I said, you know, you can make a magic mirror by putting a computer monitor behind a two way mirror. And then you can do face tracking. And so she was working on that. And she discovered that as an African-American, it wasn't finding her face. She literally had to get a white mask and put it on before the facial tracking software would find her face. And so she's like, wow, this is really interesting. And that actually led to her master's work and her PhD work on bias in algorithmic computer technology. And now there's a PBS documentary coming out about it, she's spoken in front of Congress about it, and this all sort of came out of this assignment working in the science fiction class.

Another one is Greg Borenstein. He created a machine learning algorithm that was better at discovering insider trading using the Enron data set than the legal team from the federal prosecution did when actually doing the Enron trial. And he actually went through and created a small graphic novel on how it would operate, he created the sort of web page of a [fake] law firm, you know, saying that we use this algorithm it’s this much percentage more accurate than this other law firm. But in the time since then, the real legal community is now using machine learning algorithms for legal discovery. So he was way ahead of the curve. He said this is how this is going to play out. He made a series of science fiction works that illustrated how it would play out and then in the time since, it did play out like that.

Maddie Stone: Can you talk about some of the challenges or pitfalls that you or your students run into trying to prototype technology from science fiction? Do you ever get a situation where you're just unable to replicate a technology, whether it's because it's too complex or violates the laws of physics in some insurmountable way?

Dan Novy: The number one stumbling block is somebody gets in early in the class and they want to build a lightsaber. I mean, that seems to be the one. They're like, ‘I'm going to build a lightsaber’. And I'm like, you don't have any idea how hot a lightsaber actually is. Holding plasma in your hand is probably not a good idea. And so whether it's a lightsaber or some other very fanciful [piece of technology] like teleporters, they'll get it stuck in their head that that's what they want to do. And they won't break it down into manageable steps. And you know, I'm not going to ever come out and say ‘you can't do that, that's impossible’. Because it's a science fiction class. But at the same time, you should think about possibly choosing a project that is accomplishable in one semester with the technologies that we have. And that really is the number one sort of failure mode of the class, is somebody fixates on an idea that's too fanciful and just can't be done with what we have right now.

Maddie Stone: What do you see as the next frontier for science fiction inspired innovation?

Dan Novy: I think there's going to be a lot with the brain. Neuroengineering is going to be huge. We really know very, very little [about the brain] compared to how much is there, and there’s a huge amount of sort of mad scientist level of technology required to do the most basic things. And so I think there's a huge opportunity space with neuroscience for science fiction and innovation. And then I think bio, so this idea of bio-inspired engineering or synthetic biology. There's a million things that biology does automatically and all you have to do is give it sunlight and sugar. And yet we can't we can't 3D print something as elegant as an egg.

Maddie Stone: You’ve also taught a course at MIT called Indistinguishable from Magic. Could you tell me a little bit about that course?

Dan Novy: Yeah. So it is based on the Arthur C. Clarke quote that any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic. And originally it was kind of a funny thought of, okay, we've got the science fiction [course]. But what about fantasy literature? What about Harry Potter? What about Dungeons and Dragons? Could we make a fantasy literature version of this class? And in a way, I think of it as sort of a left branching isomer of the science fiction class in that they're actually the same thing. But often magic is science fiction where you don't have to explain how it works. And so if we were going to figure out how to make a sufficiently advanced technology that appeared to work as magic, how would you do that?

And so I will often hand someone in the class the D&D Player's Handbook and say, I want you to build a spell. I want you to make one of these spells real. And so I had a student for a final project who was a lifelong D&D player, and she loved the light spell. Like, this is like one of the most basic spells in D&D. You cast light. It's a blob of light that floats above your head but is hand tracked, so you can move it around. You can push it where you need it, you can pull it. And so she built an incredibly bright LED on a drone with a camera pointing that was doing hand tracking. So the drone takes off, tracks her hand, floats above us and there’s light. So we turned out all the lights in the room and there was just this floating ball of light that tracked over her head. And I'm like, that is the light spell. You did it.

Maddie Stone: I could see a lot of applications for visual effects for movies here.

Dan Novy: Yeah, and visual effects themselves are a form of magic. A lot of early films were actually shown in magic parlors. There's this deep, deep, connection and relationship between magic, stage magic, the film industry and especially visual effects. I mean, film itself, it's twenty four still frames that your brain is turning into motion. That is an illusion. It's illusion engineering.

Human centered design can learn a lot from magic design and stage illusion. You know, magicians have been hacking the human cognitive and human visual system for 5000 years. They know a thing or two about how people think and perceive and feel. And so when you're creating an application or a piece of technology, if you think like a magician, if you present the information to the audience as a magician would, then you're actually going to understand what it is that person is expecting to see, what they're expecting to feel. A magician would say, they don't need to see that part there. That's completely that's behind that's behind the curtain. What you're going to see is the result. And it should be clean and fluid and understandable and without extraneous elements. And that's what a magic trick is. It's an effect where the extraneous elements, how it's done, all the machinery or the methods are hidden essentially because the audience doesn't need to know that. What they want is that moment of surprise and delight, which is what you want when you click on something [on a computer or an application]. You're like, ‘I want to play this song’ or ‘I want this to download’.

Maddie Stone: So you're sort of trying to articulate the scientific basis for magic.

Dan Novy: Yeah. Essentially.

Top GIF: The Chanel makeup machine from The Fifth Element was the inspiration behind “Glitter Machine,” another recent student project from MIT.